Voices

For many survivors, the war did not end with liberation. Usually left to their own devices, they had to come to terms with their experiences of persecution and rebuilt their lives. They were often unable or unwilling to return to their homes, or were displaced and spend years searching for a new home.

Not just physical survival

»Survival doesn't just mean physical survival. I remember when the war was over, one couldn't go from one extreme to the other: The feeling of sheer hopelessness, the suffering and the discrimination can't simply be erased just because the war was suddenly over.«

Sabina van der Linden-Wolanski (1927 – 2011) survived deportations and mass shootings by the SS in the eastern Polish town of Borysław. After liberation by the Red Army, she was forced to leave her now Soviet homeland and emigrated to Australia in 1950.

Our children are coming

»I will say in conclusion what is most beautiful to me, even though war is the most hideous thing that can happen to people. […] We walked terrified that Warsaw looked like, that the uprising had failed. And then the civilian population stood along Jerozolimskie Avenue. [...] While we were walking broken, afraid to raise our heads and look at those people, they were crying and shouting: Our children are coming.«

Wanda Traczyk-Stawska (*1927) was a girl scout. She took part in the 1944 uprising in her home town of Warsaw as a riflewoman and liaison officer for the Home Army (Armia Krajowa). After being seriously wounded and suppressing the uprising, she was captured by the Germans and imprisoned in camps.

I was completely exhausted

»I was completely exhausted in every sense – physically, mentally, morally. [...] Good heavens. One has survived for so long and now that the Americans are here, one is supposed to die? [...] At some point I finally managed to pull myself together and got out of bed very, very slowly. I got as far as the exit door. There my strength left me and I slid to the floor.«

On 5 May 1945, US soldiers liberated Sinto Reinhard Florian (1923 – 2014) from the Ebensee subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp, but he could not return because his home in northern East Prussia had been taken over by the Soviet Union.

But us? Why did we have to suffer too?

»We had managed to save ourselves from the Nazis, but not from the coming disaster. What a disappointment that was for us! It was to be expected that Russian soldiers would throw themselves at the Germans in a rage. It was revenge for what the Germans had done to the families of the Russian soldiers. But us? Why did we have to suffer too? And all this was just the beginning.«

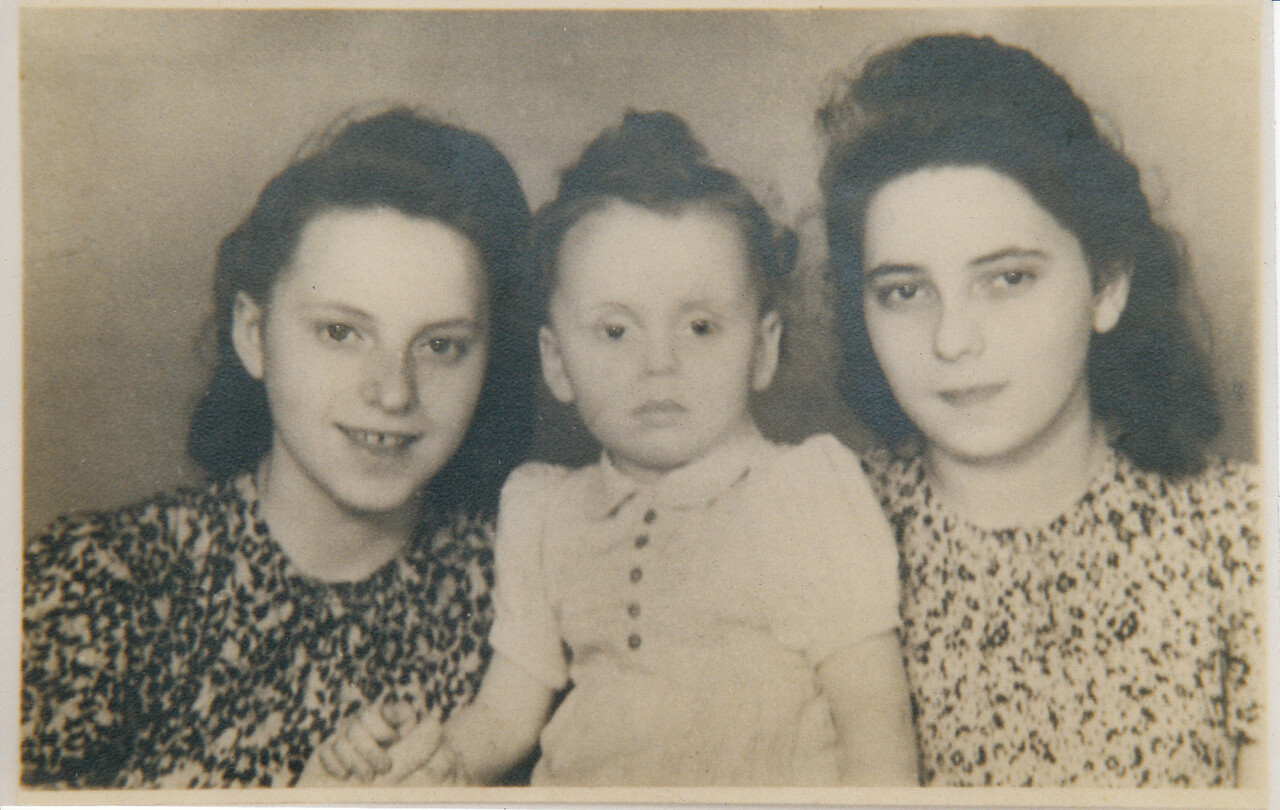

Nechama Drober (1927 – 2023) was born as Hella Markowski in Königsberg, East Prussia. She was a slave labourer and was a witness to the anti-Jewish pogroms of November 1938, the two deportations in 1942 during which she lost family members and school friends, and the destruction of her home town by bombing in the summer of 1944. In the quote, she describes her thoughts in the face of the atrocities committed by Soviet soldiers on 28 January 1945. She lived in Israel from 1990.

Traumatised

»I was probably so traumatised by everything I had experienced that I became addicted to alcohol. [...] When one is traumatised, it's difficult or impossible to recognise the causes.«

Ludwig Baumann (1921 – 2018) deserted in 1942 in resistance to the German war of annihilation in the East and was sentenced to death. In 1990, he founded the Federal Association »Victims of Nazi Military Justice«, which achieved the blanket rehabilitation of Wehrmacht deserters by the Bundestag in 2002.

An end to hatred

»Once again we see tanks. This time they promise freedom, redemption, a new life, an end to hatred, to evil, to bloodshed, to the mistreatment of innocents. We have made it. The camp gate is open. I step out without fear of being caught.«

Esther Wallheimer (1928 – 2008) returned to her Polish hometown of Łódź after her liberation by the Red Army from the Kratzau (Chrastava, today: Czech Republic) sub-camp of the Auschwitz concentration camp on 8 May 1945 and emigrated to Israel in 1948.

Something withered inside me

»100 days had passed between my separation from my mother and the day of liberation. 150 days of hiding, which had led to my rebirth. But now, after the liberation, she didn't come. Why couldn't I meet her straight away? Mum never showed up again and something withered inside me, something that refused to give up waiting for her for years, the hope that she would come and get me back.«

Thanks to his mother Lea, Shalom Eilati (*1933) managed to escape from the ghetto in his Lithuanian hometown of Kovno (Kaunas) in March 1944, to which they had been forced to move in the summer of 1941. He stayed with Lithuanians until his liberation by the Red Army. In 1946, Eilati emigrated to Palestine via Munich.

I should not return alive

»I took part in the death march. I marched for ten days. I wasn't supposed to come back alive. [...] Ten days of misery – that's indescribable. [...] until the International Red Cross came through and they put an end to it. I was near Schwerin then. That's where I was born the second time.«

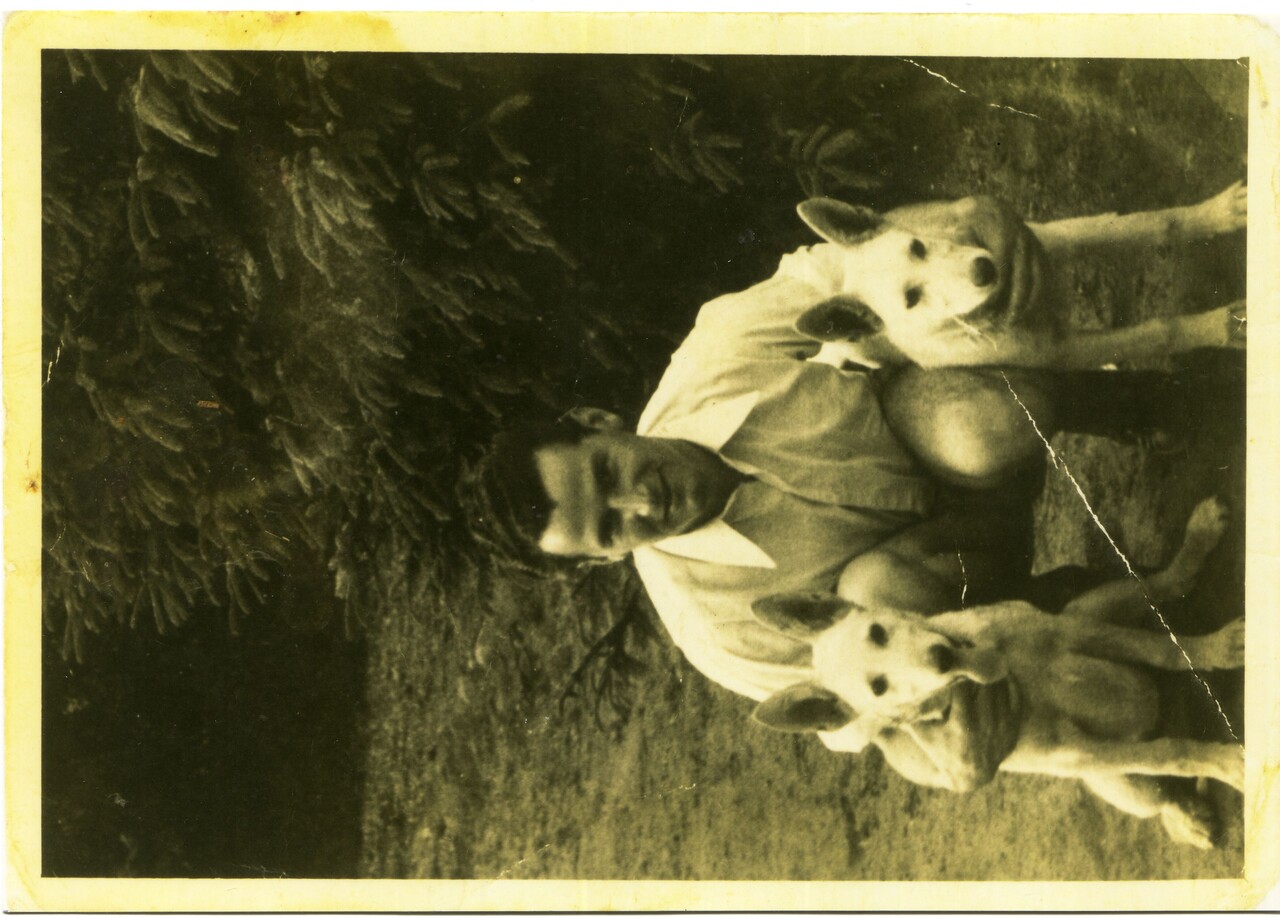

Ab Nicolaas (1917 – 1999), a resistance fighter from Leiden in the Netherlands, survives almost four years in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. He began a new career as a clown and quick-drawing artist. He gained his first experience as a clown in the concentration camp performing for his fellow prisoners.

Have we become so numb that all this leaves us calm?

»Yes, this time it really is true: our oppressors are gone, we have nothing more to fear from them. We are finally free again, not yet completely, but at least the heaviest pressure is gone. And strangely, our joy is not expressed in loud demonstrations [...]. How often have we imagined this moment in the years of our servitude. And now everything has turned out quite differently. Are we so numb that all this leaves us calm?«

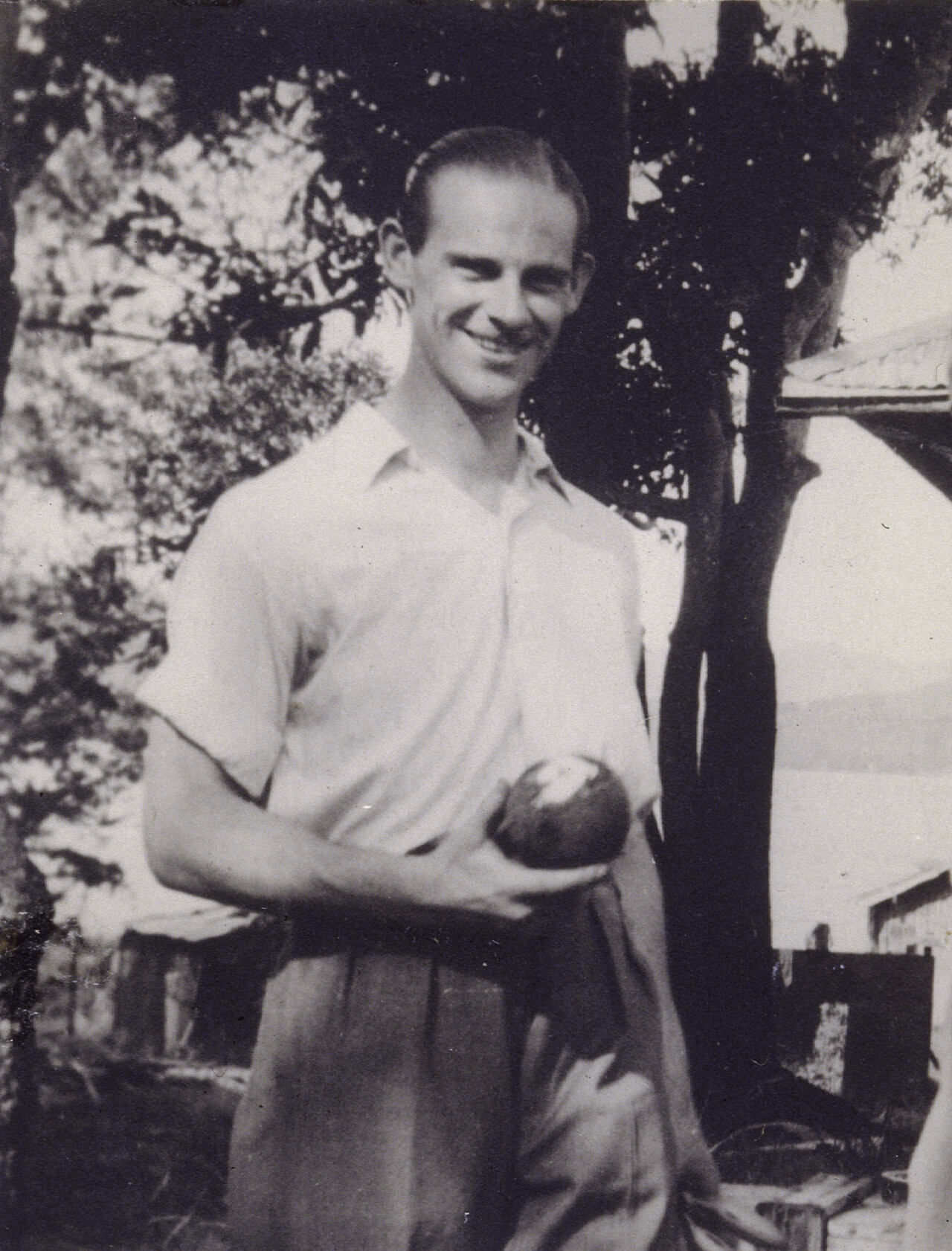

Henri Michel (1900 – 1976) was a Belgian patriot and journalist who was arrested in September 1940. In Sachsenhausen concentration camp, he belonged to a group called the »Journalists' International«. After 1945, he resumed his pre-war activities as editor-in-chief of the German-language newspaper »Grenz-Echo«.

Strange love of one's homeland

»The final victory is when the Allies enter through the Brandenburg Gate. And again I think, as I have so often before: What an absurdity that a German prays for the victory of the enemy! Strange love of one's homeland which can wish for nothing better than to see it conquered.«

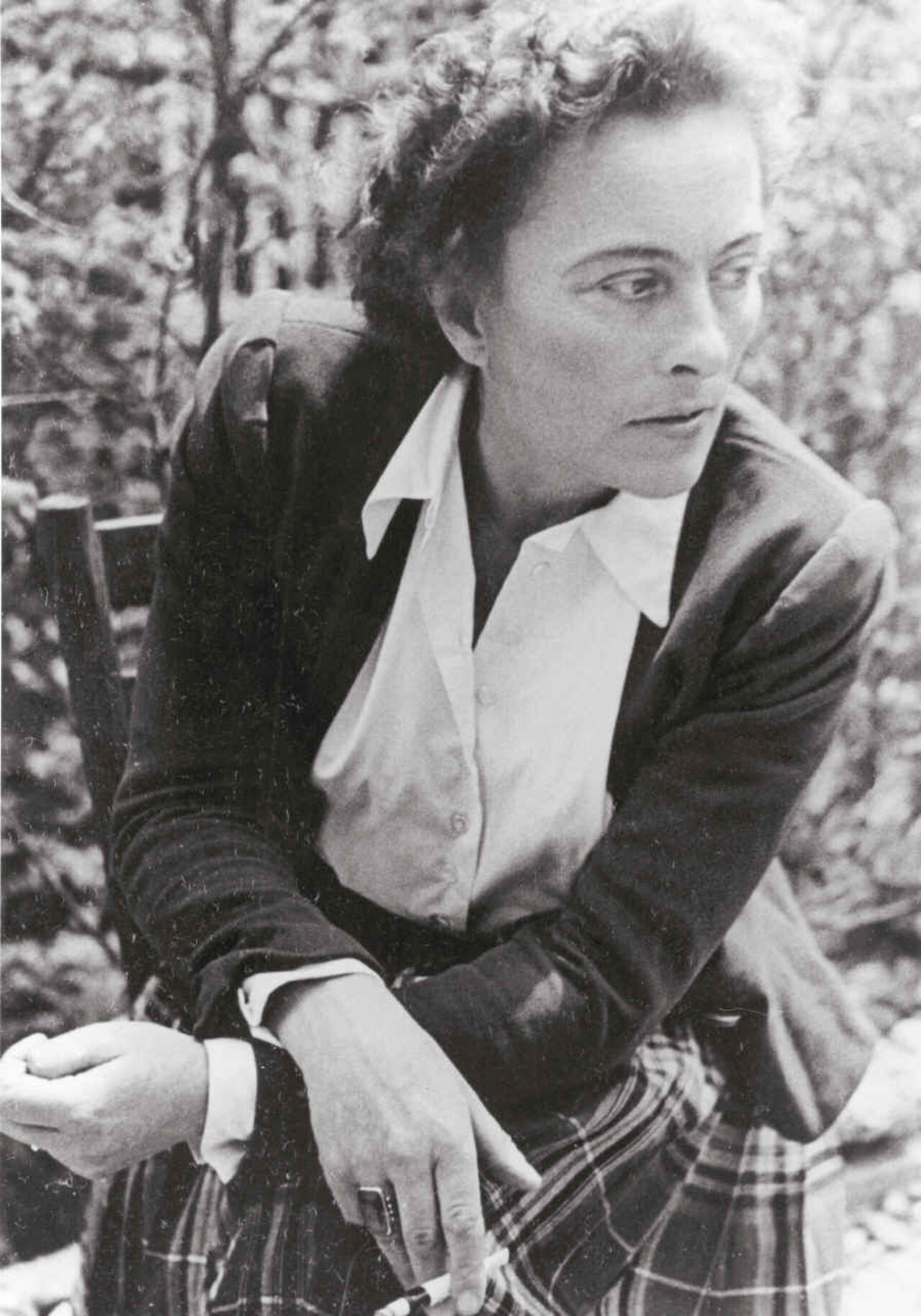

The journalist Ruth Andreas-Friedrich (1901 – 1977) was part of the Berlin resistance group »Uncle Emil«, which supported persecuted Jews. On the night of 18 to 19 April 1945, they wrote »NO« on the facades of houses in the south of Berlin and distributed numerous leaflets two nights later. The diary entry is dated 31 March 1945.